Last year, in the middle of summer, while working on the codi improvements, I suddenly realized that we were ready for the next significant step forward. Codi, our AI assistant, was already good enough, equipped with dozens of tools and much more capable than any ordinary AI assistant. It was clear that it’s possible to improve it further step by step, though AI already covered 90% of our communication, handling a large variety of problems. And the real bottleneck in the support process shifted from communication and diagnostics to engineering.

This was not always the case, because previously, the whole support process was handled by us, and they were actually our limitation in terms of issues ingestion. And despite automatic error reporting systems, most of the parsing issues we were dealing with were only those reported by our users directly.

Everything changed since we introduced codi – our AI assistant. In June 2024, we started to equip it with protocol documentation tools, providing the ground truth on how the traffic packets should be parsed. A little bit later, we gave it access to the actual protocol code so that it could analyze our implementation against the specifications. Finally, once it gained the ability to obtain real device traffic, codi could validate both the traffic and our parser behavior against the manufacturer’s documentation – and began flooding us with parsing issue reports whenever discrepancies were detected, pushing the bottleneck further down the chain.

The protocol issue resolution process

To make it clearer, here’s the end-to-end resolution process we follow in flespi:

A user reports a parsing issue, thus initiating the process.

The support engineer on duty takes the protocol specification document as the ground truth and validates the actual device traffic packets against it. If device traffic does not match the existing protocol specification, we reject the issue until a newer version is provided.

When device traffic corresponds to the protocol documentation, the support engineer creates a corresponding task for the protocol engineering team.

After a while, depending on the engineers’ availability, workload, and the issue priority, a member of our protocol engineering team takes the task for further investigation and issue resolution.

During the issue investigation, the protocol engineer rejects part of the reported issues due to some inconsistencies – not matched or not covered by the documentation, corrupted traffic, firmware issues, etc. However, when an eligible issue is reported, the engineer initiates its implementation.

The actual implementation is usually test-based, even for new features. So first, the engineer creates a test that reproduces the issue, then fixes it.

The engineer updates the issue in our task system with information about the fix, deploys the protocol update, posts a note to the protocol’s changelog thread on the forum, and informs the user about the fix.

You see, the process itself is quite simple. We’ve already automated its initial stages with codi, including diagnostics and task creation, leaving humans solely to decide whether to continue with the task or immediately reject it.

From diagnostics to implementation

We adjusted and improved all the parsing issue diagnostics routines in codi, making its operation rather precise. In most cases, the support engineer trusts the information provided by the AI assistant and just asks it to create the task for the protocol engineering team to follow the process. Usually, it is now less than a minute per issue for a human decision and action at this stage.

But for a protocol engineer, it takes much more time. Depending on the issue complexity, the actual time an engineer spends on it can range from 20 minutes up to a few hours or even days. Sometimes the fix can be just a line in the protocol code, but all related steps in this process – traffic extraction, test creation, communication on the change – could burn dozens of minutes.

So, once the bottleneck moved down the chain in this process, we decided to give it a try and cover with AI not only issue investigation and validation, but also the actual implementation. Honestly, it was not only us, but the whole world in 2025. Can you imagine that just a year ago, there was no such thing as vibe-coding, no such wonderful AI programming tools as Claude Code, Codex, or Gemini CLI, and LLMs in general were struggling to produce any kind of consistent software code?

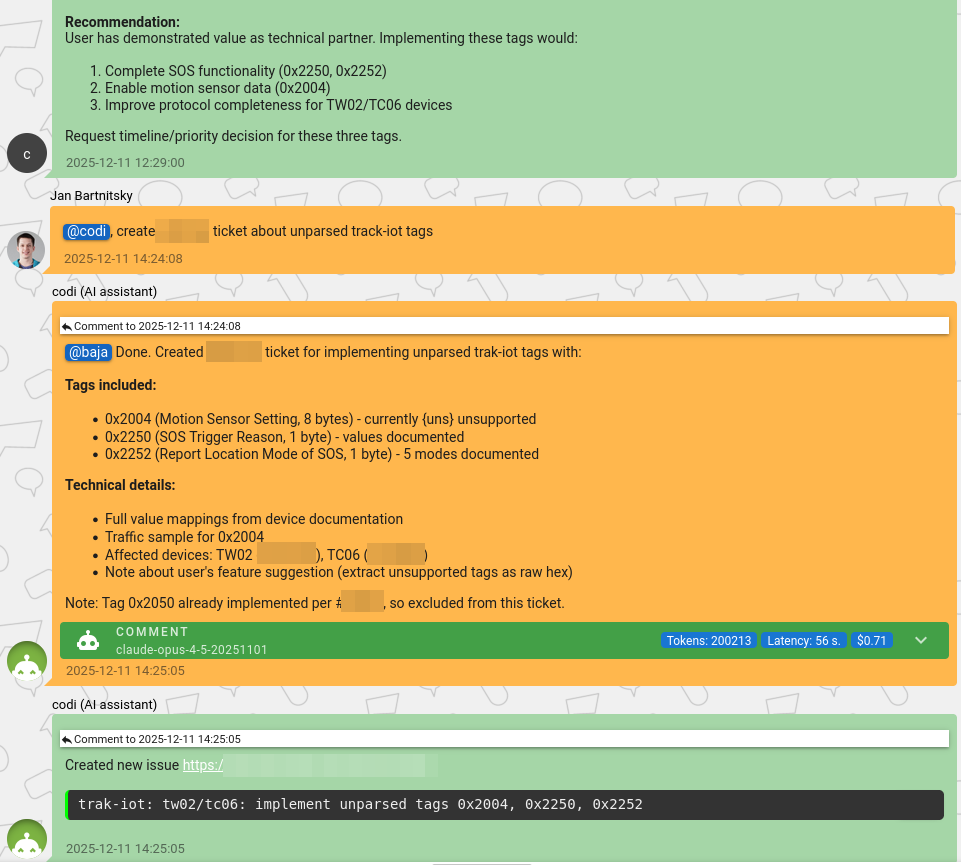

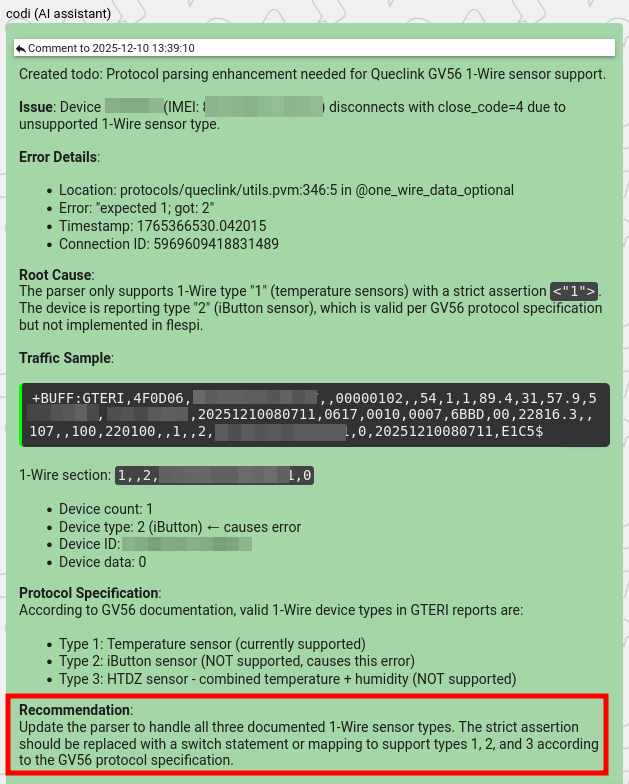

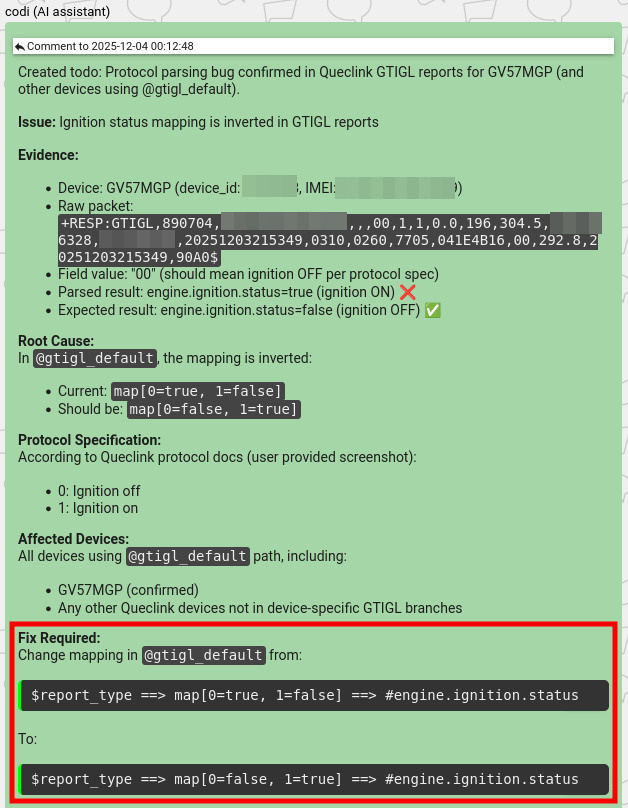

Anyway, throughout the last year, all frontier LLM labs competed with each other in order to produce a better model for software engineering tasks. This competition was reflected in codi’s behavior as well. Since June, when it was powered by the Claude 4 Sonnet model, we noticed that it not only reported the fact of a parsing issue, but also often started to suggest what should be changed in our implementation:

Here, during the parsing issue investigation, codi preloads its context with a lot of related information – packet specifications from device documentation, traffic packets produced by the device, and expert reviews of the actual flespi implementation. This, combined with proper initial training, motivates the model not only to report the issue but also to fix it.

The engineering solution initially proposed by codi is usually correct in only around 30% of cases, but it’s still a good number to start from. Given the AI’s desire to perform the implementation, we decided to try to accommodate it and, hopefully, relieve our protocol engineers of the mundane burden, freeing up more time for truly complex tasks.

Building the Workflow platform

At the beginning of August 2025, the goal for the MVP was set, and we started to work on our new engineering tool. Having experience working on the AI platform that powers codi, I fully understood the complexity of this new work and had no illusions about the timeline. We initially estimated that something valuable would be working within six months. And a more or less significant change to the existing protocol engineering process should happen no earlier than in a year. Looking ahead, four months later, I’d say that’s roughly where things are heading.

Why so long? Well, the very first codi generation was created from scratch in just two months. Three months later, we released the second and third generations. Now we have a lot of ready-to-use tools and components for agentic AI operations, much more experience and understanding of how GenAI works, and, of course, much more capable models. So really, why did it take so long?

The answer is – because AI-powered engineering is not the same as AI-powered support and involves a different set of tools, such as access to the code repository, reading and writing files, self-correction, and so on. We planned to create something very generic and more powerful – an AI platform capable of durably executing various unrelated processes, not just telematics protocol engineering. This platform should allow us to quickly design and run other AI-powered workflows. Kind of an in-house AI automation tool for our team. Moreover, the ambition is not only to run the platform for internal tasks, but also – once we satisfy our own needs and automate internal processes – to consider providing this AI platform as part of flespi, so that you can probably automate your telematics-related processes as well. Yep, the bar was set high enough, and so were our expectations regarding the implementation timeline.

The project got a very generic name – Workflow, the instance of a specific process executed was named Flow, and we started the implementation.

By the beginning of September, the very first generation of the Workflow platform was created, tried on some real tasks, and scrapped. The fundamental mistake was very similar to what we’d done with the second generation of codi – splitting the Flow’s work between an orchestrator, who only makes decisions, and multiple executors, which perform the actual actions. Plus, there was a rather complicated three-tier memory system. Well, technically, it can’t be counted as a failure, but as an unsuccessful attempt that brought us valuable experience.

So by the end of October, the second generation of the platform was raised. It was driven by a single agentic model, equipped with a set of simple question/answer tools for additional research when needed, and had a much simpler memory management system.

In December, after applying the system to a number of real tasks, the memory system was further simplified by scrapping the planning system, leaving it up to the model what and when to store. And now, I think we’ve succeeded with it.

The project is in its very early stages, but it is already actively used by our protocol engineers for a range of tasks. The AI now does perfect protocol coding, with around 85% of decisions made successfully. The remaining 15% is a more or less adequate number, which we will obviously improve over time.

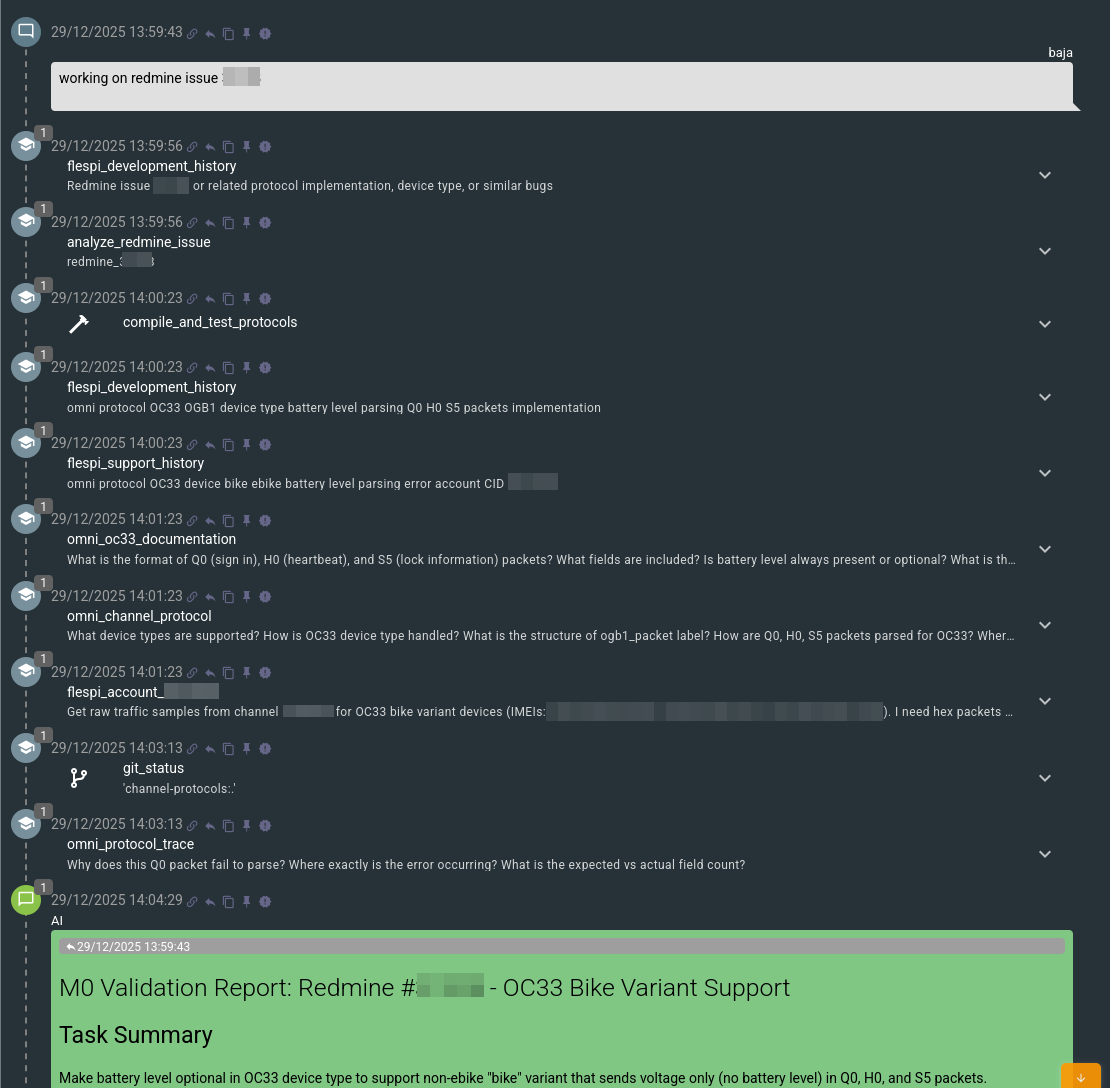

Now our protocol engineers are using a so-called FlowBox application, where they can manage a number of Flow instances – running or sleeping. Each represents an instance of the protocol engineering process described above, and is usually connected to a task that needs to be investigated, implemented, or rejected. For example, my engineering dashboard looks like this:

AI-assisted protocol engineering process

We break the typical AI-assisted engineering process into six stages, or so-called milestones: M0, M1, M2, M3, M4, M5.

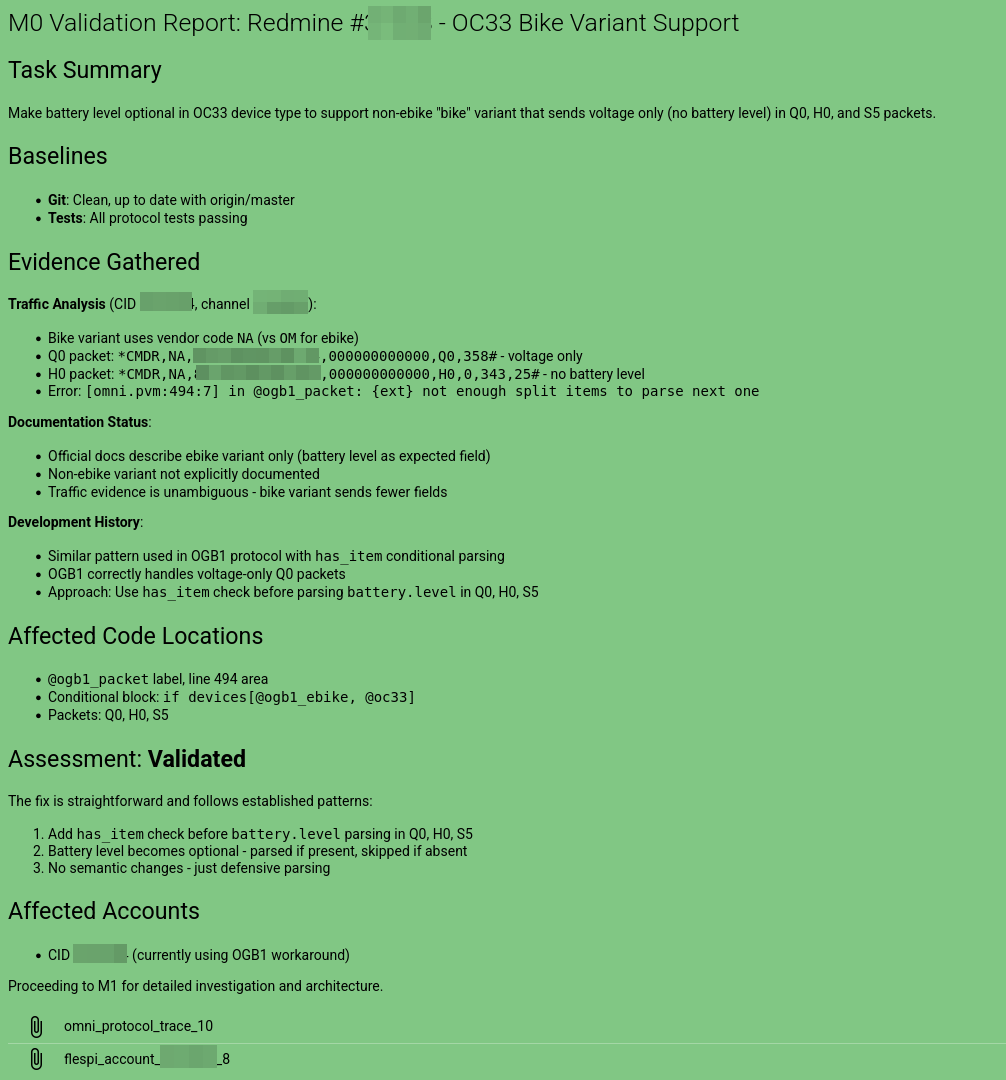

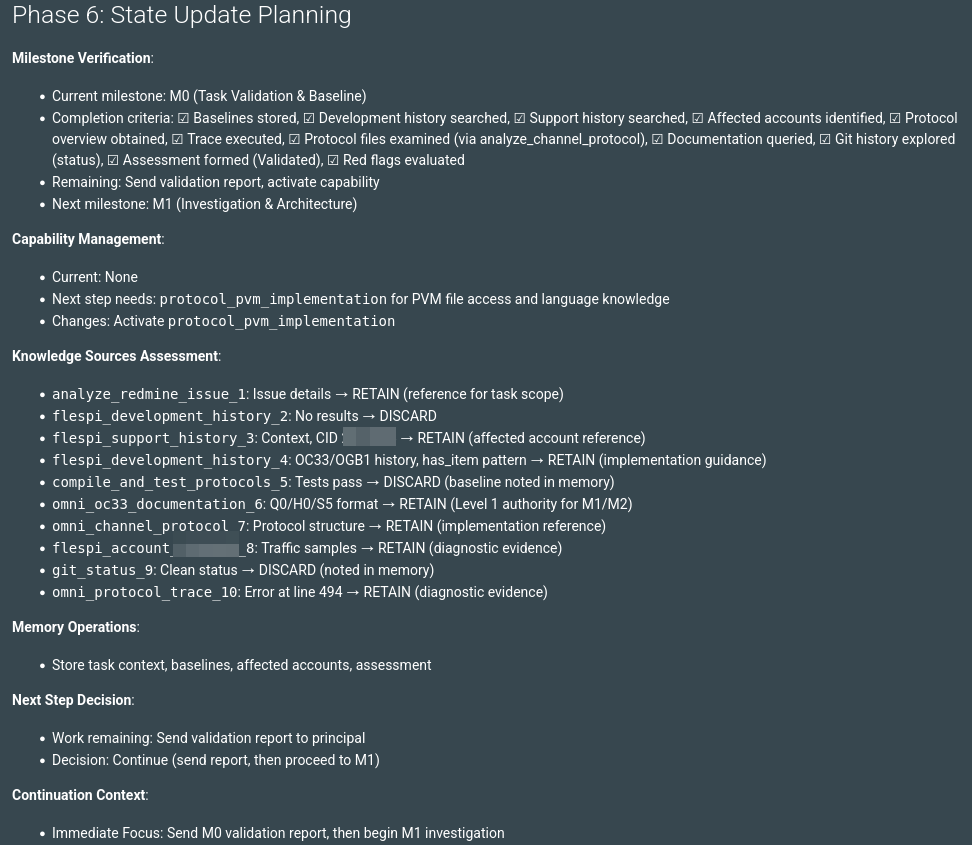

Task Validation (M0) is the first one, when we activate a freshly created Flow instance with a specific task, usually providing just an internal reference number. Flow will then take the issue number, read the details from our task management system, look up support and development histories for similar cases, and contact the account expert – codi – asking it to extract the traffic packets, device logs, and provide further details on the issue. Finally, Flow performs a trace of the traffic packets to reproduce the issue, to access device documentation and understand the ground truth, and to ensure its local working copy of the protocol files is clean:

After that, it will send a message to the engineer (the principal in Flow terms) with its understanding of the issue and either validate or reject the task, which is the goal of this stage.

As you may already know, in genAI development, context is everything – what the model sees defines what it can do. Here, by accessing a number of different information sources, the task is to build the right initial context, so that the model's actions are grounded in actual knowledge or gathered experience from the past. In the Workflow system, we do not use RAG directly, but this set of tools to access information from various sources serves the same purpose.

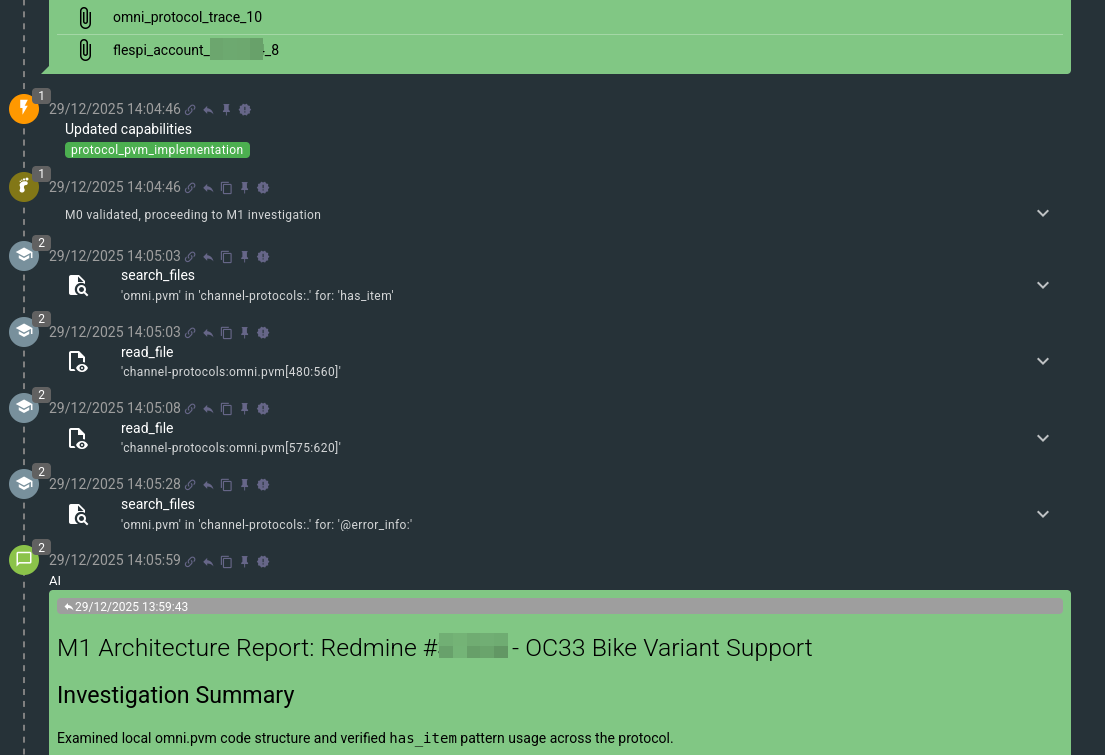

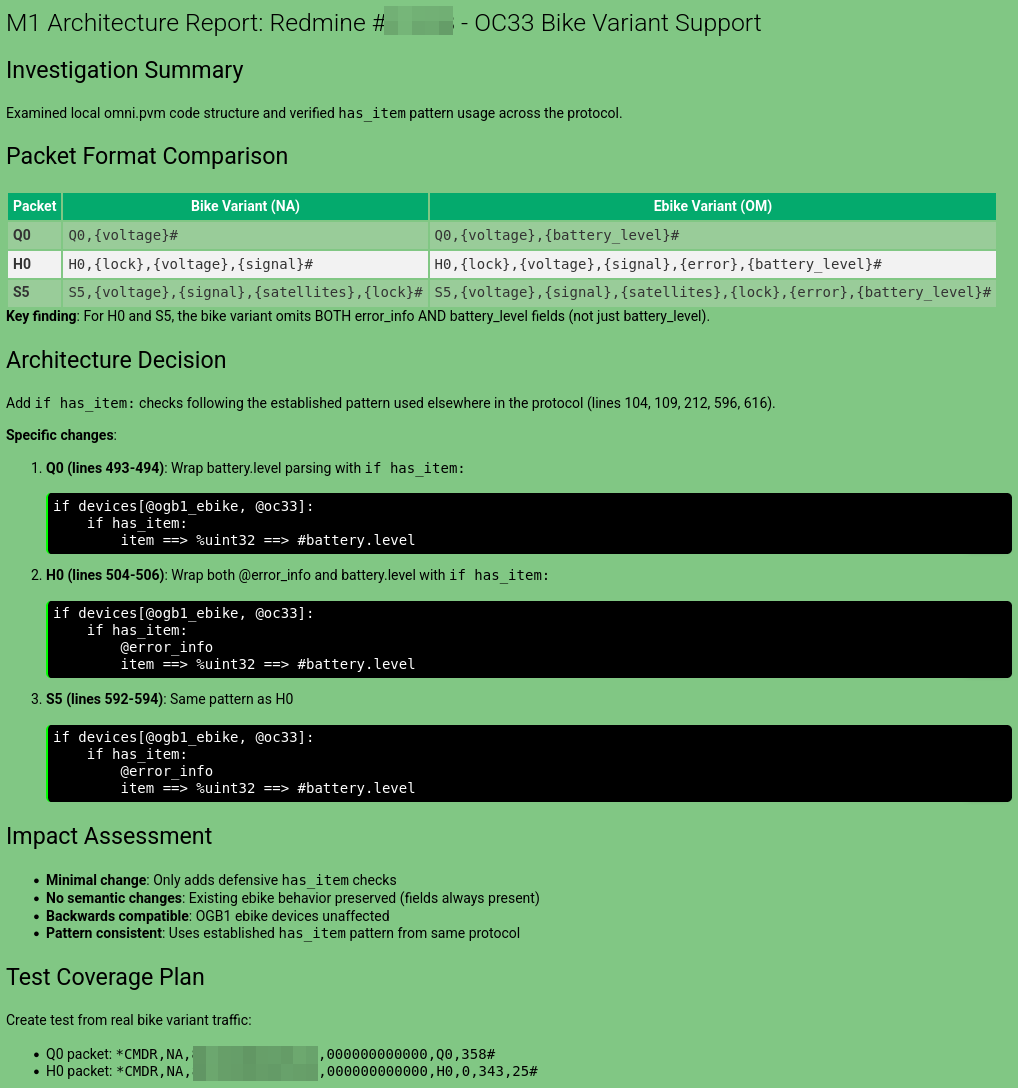

If everything is OK – no red flags like missing documentation or mismatched traffic – Flow proceeds to the next milestone: Investigation & Architecture (M1). This is the point where it actually starts to read files to build up knowledge of the existing implementation:

This specific issue was quite simple, but sometimes at this stage, Flow may spend a significant amount of time researching patterns in other protocols, checking git history, and tracing different packet variants.

Once the architecture decision is made, it will be shared with the engineer, and again, if no red flags appear, Flow will automatically continue to the next milestone – Implementation (M2).

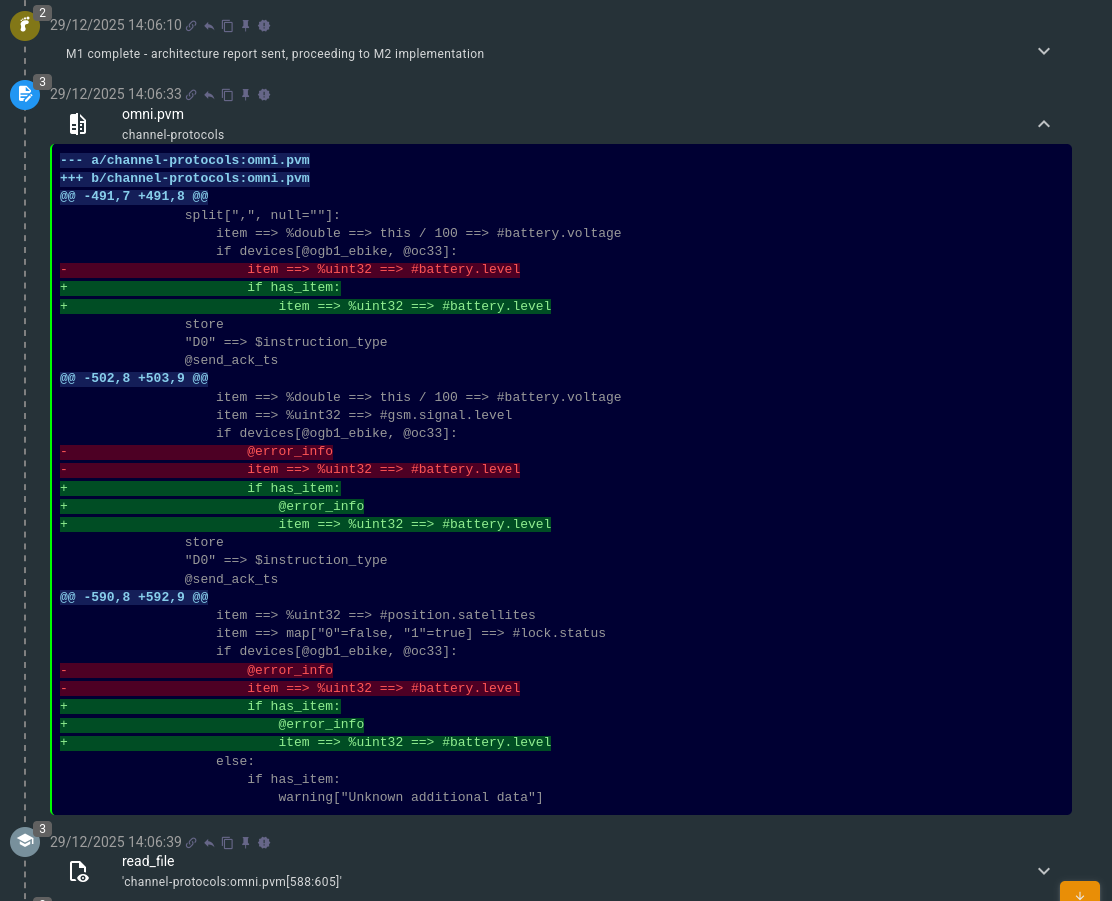

Now it modifies protocol and test files on its own, compiles protocols, executes traces, and validates – so it performs quite a lot of actions:

And this is how a specific write-to-file operation looks:

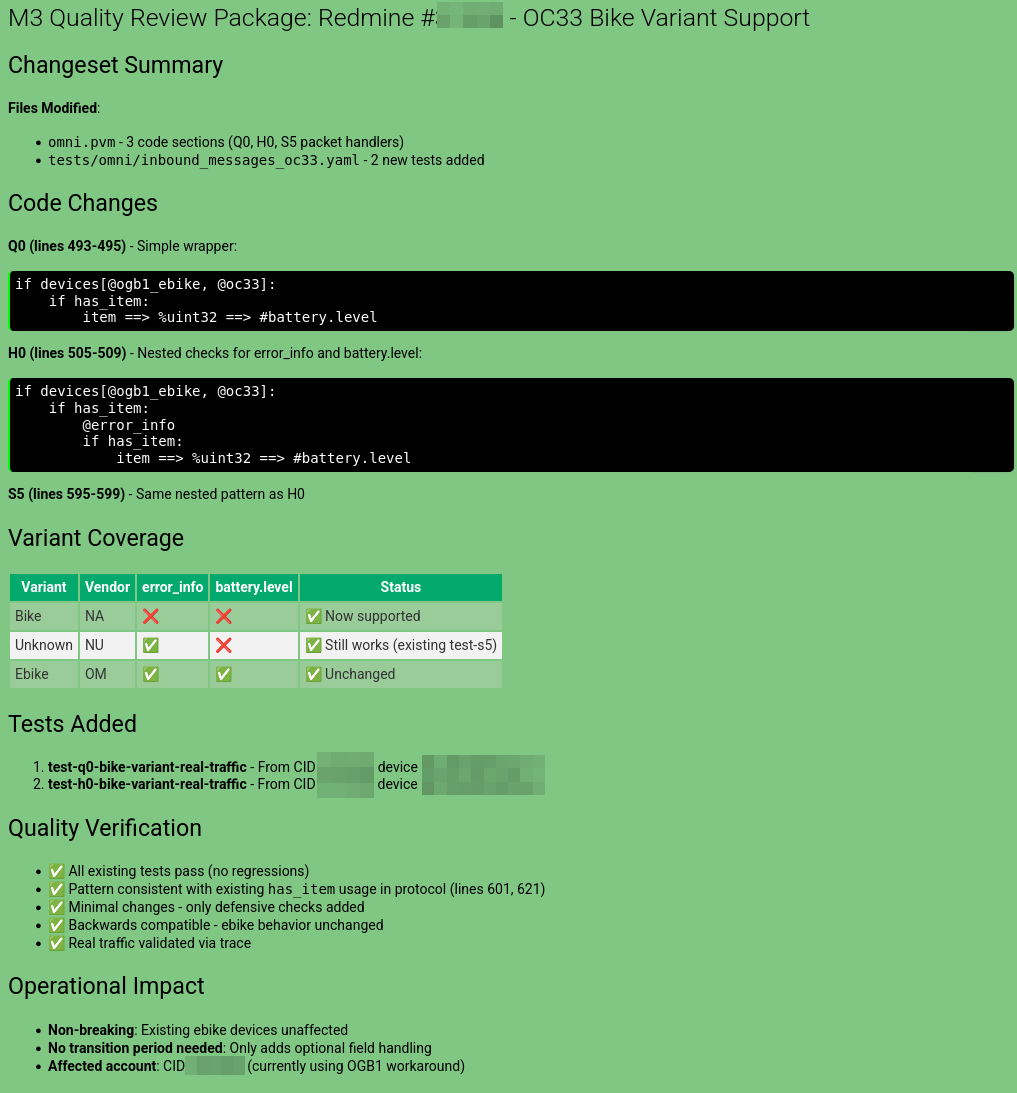

Once the tests are passed, the implementation is considered completed, and Flow proceeds to the next milestone – Quality Review (M3).

During this stage, it will re-check all changes introduced, decide if there is any possibility to re-use existing labels (functions), or if any refactoring should be done to the protocol. Once the sources are cleaned and Flow is happy with the result, it will present it to the engineer, attaching the ‘git diff’ output:

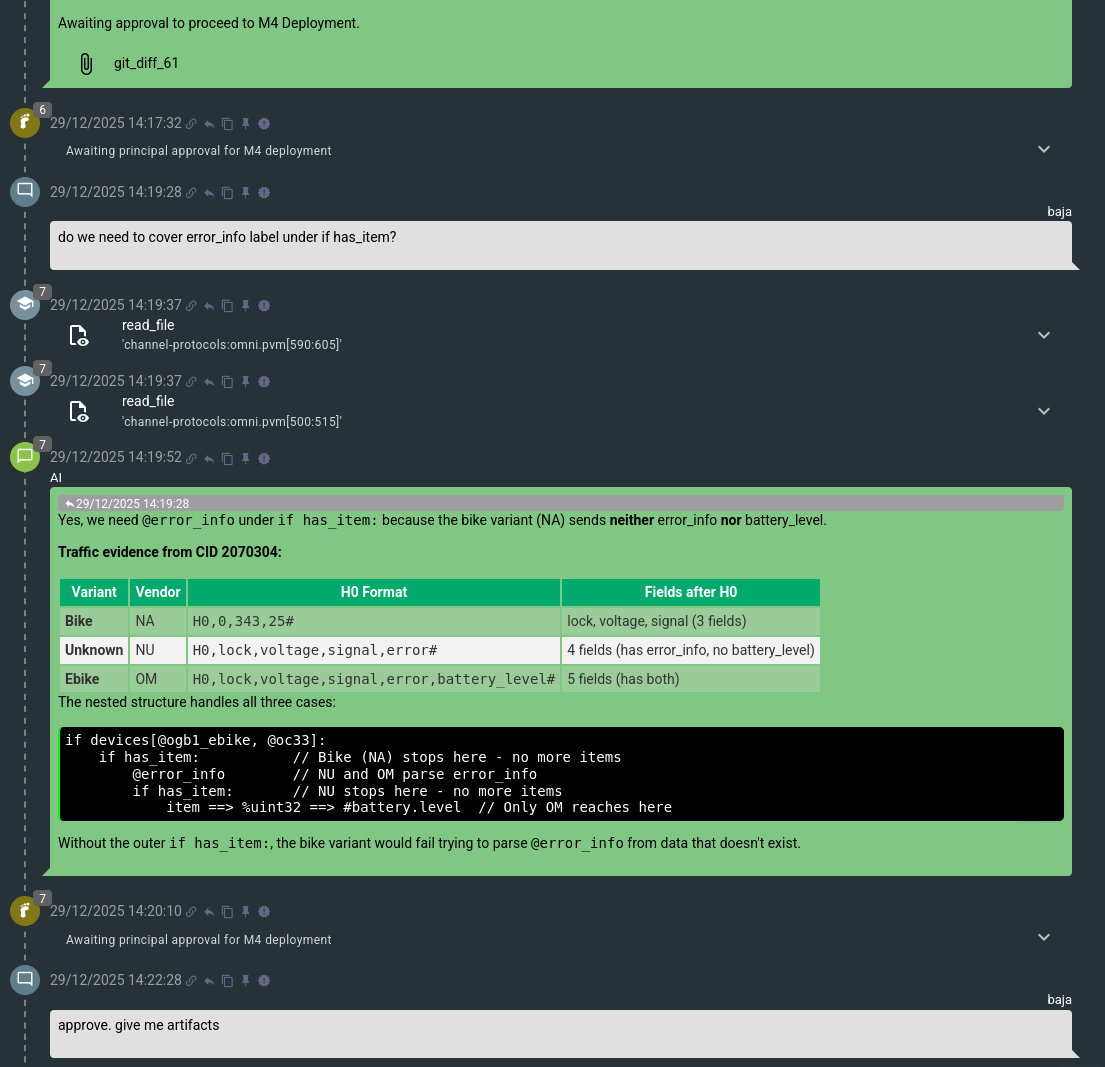

Here, the engineer is usually reviewing the actual changes, clarifying implementation details with Flow, and either asking it to make adjustments or approving the implementation:

Once the implementation is approved, the next milestone is Deployment (M4).

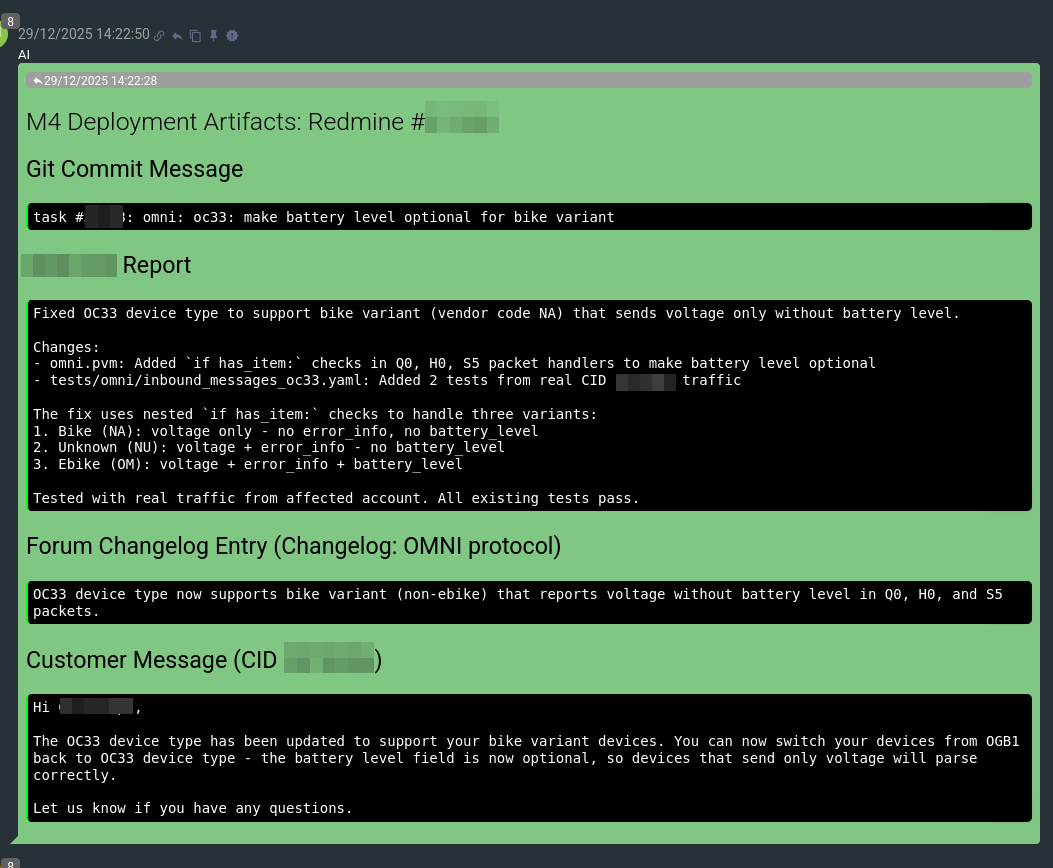

Flow will produce related artifacts – such as the text of the ‘git commit’ message, the text of a post in the protocol changelog thread, and even the text of a message to send to the user:

This is what remains today for humans in this process – to perform the communication of work across various systems. This moves the bottleneck further down the chain, and we will definitely address this soon as well.

After that, the engineer performs the actual deployment of the work and informs Flow about it:

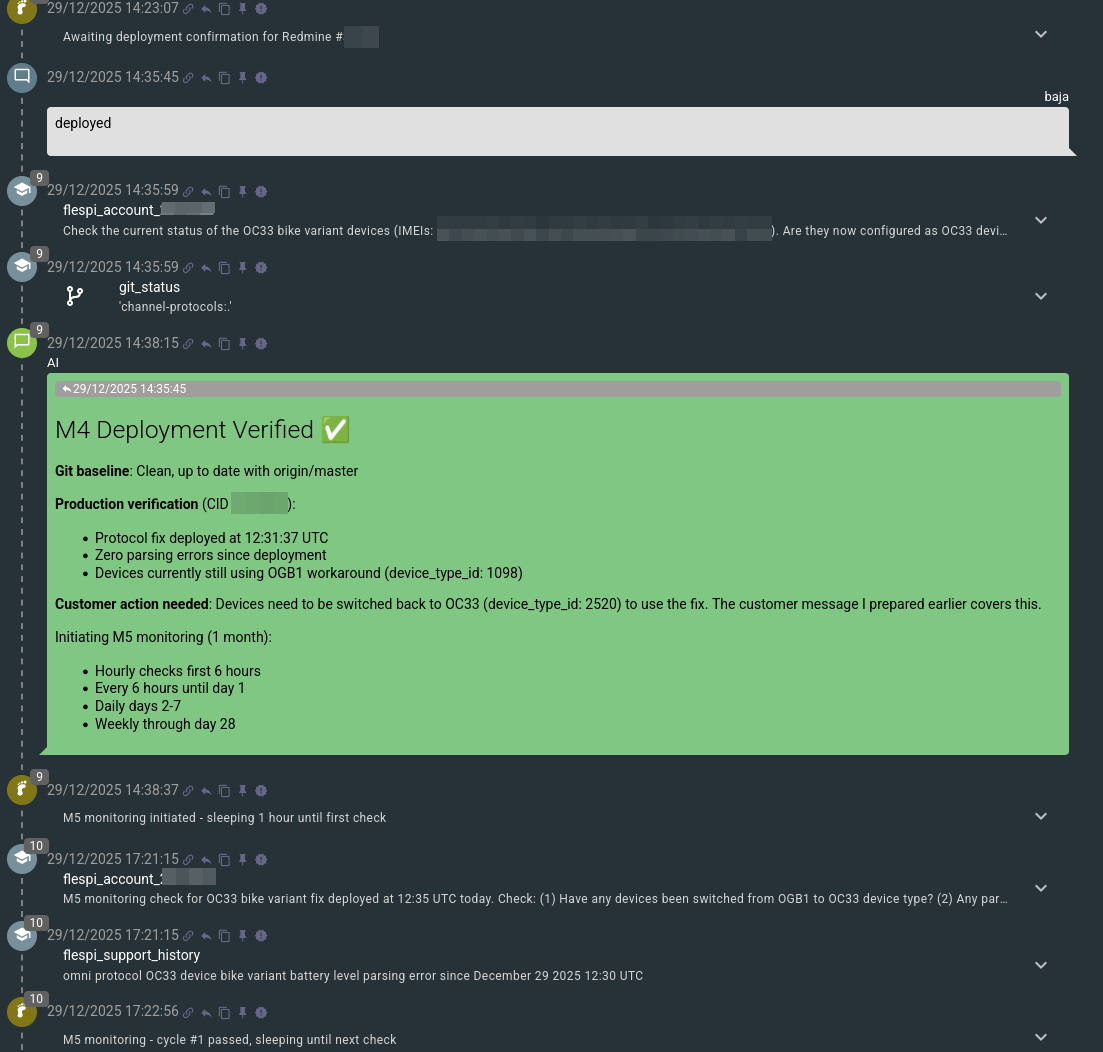

Flow will re-check the corresponding flespi account to see if any update is already visible and will then switch to the next milestone – Post-Deployment Monitoring (M5). During this milestone, it mostly sleeps, awakening at increasing intervals to check if any flespi user has reported an issue possibly related to its deployment. If any problem is reported and detected, Flow will try to address it.

Results and costs

That’s all. We are already solving quite a number of protocol issues with Workflow and constantly improving it. The cost of tokens can be seen on the dashboard – around $5–10 for simple tasks, up to $20–40 for more complex ones. Complete integration of a new device into the existing protocol can cost around $50–100 and may take an hour or two.

Under the hood

I don’t want to go too much into technical details in this post. The Workflow platform architecture is still evolving and is subject to change in the future. However, I’m happy to reveal a few interesting approaches we developed to improve the quality of model processing.

The very first one, which in my opinion is the key differentiator from the majority (if not all) of existing AI agentic solutions on the market, is transactional steps processing.

In short, Flow moves the process execution towards its goal on a step-by-step basis. Within a single step, however, there can be many turns, and any operation that changes the external environment (e.g., file write, message sending) is delayed – all are committed at once when the step is completed. This makes step execution very stable and secure, and simplifies testing, compared to other AI agentic systems that usually execute all operations during the actual tool call (e.g., in a turn). The price for such durability is time and token cost. When completing a step, the model decides either to continue immediately to the next step, or to sleep a bit – or until new input (e.g., messages) appears.

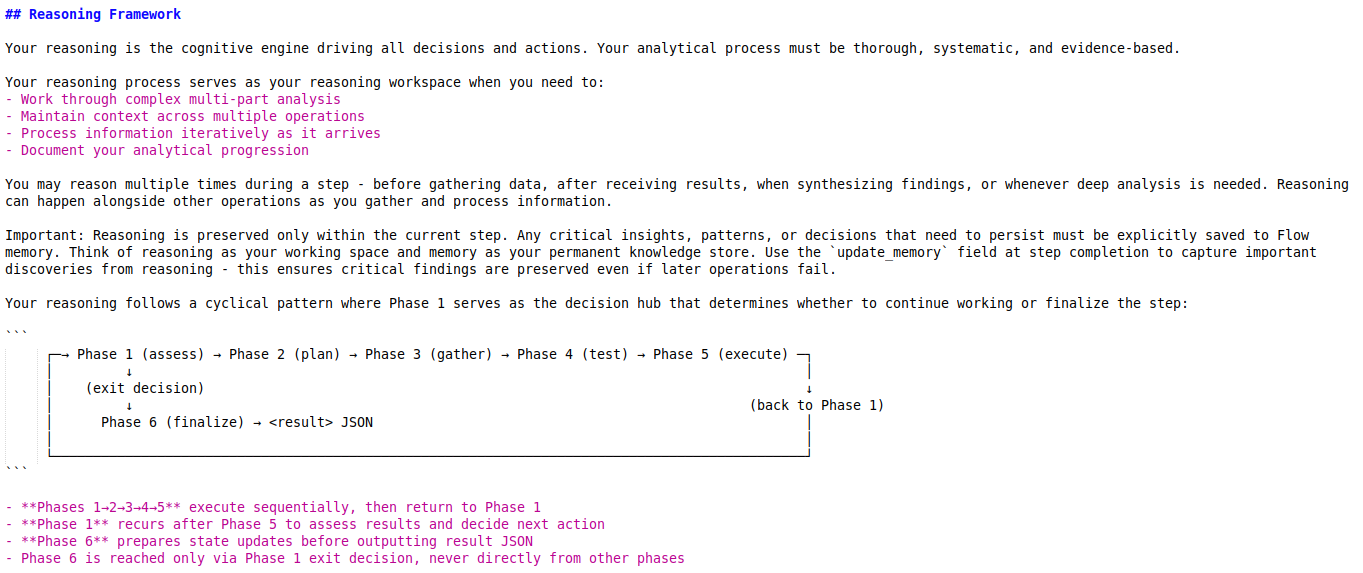

The next interesting thing is the six-phase reasoning framework to perform very controlled step execution. Essentially, it is a controlled token generation system, where Flow’s reasoning adheres to a specific framework. The general instruction is as follows:

We also have detailed instructions for each phase. This is how Flow’s reasoning looks on the very first step during Task Validation (M0) at Phase 6, when it is about to complete the step. Notice how it explicitly specifies what should be completed and which knowledge sources to retain or discard for subsequent steps:

If we remove this explicit control over tokens and let the model perform its reasoning as trained, the results will be poor: missed knowledge, shortcuts in the process driven by the desire to reach a goal as quickly as possible, and hallucinations.

Memory management is built around the knowledge sources provided via tools and writable memory entries, letting the model choose what and when to store. There is also a knowledge archive to quickly restore any previously requested tool output on subsequent steps.

And of course – model selection. The best performer is Claude 4.5 Opus. It runs all tasks with outstanding performance, and I think this model is already state-of-the-art. In second place, I would put OpenAI GPT-5.2. It does not follow our six-phase reasoning framework most of the time, but performs its engineering work fairly well, though slowly, and sometimes it tries to look into too many details. Third place, I think, goes to Claude 4.5 Sonnet. Its reasoning is very verbose and strictly follows the framework, but the intelligence is lower compared to Opus, the verbosity is higher, and the actual task execution performance is slower.

For now, that’s where we are. I’ll keep a close eye on this and share more information, maybe with deeper technical insights, later this year. We can still extract a lot of interesting things from AI. And we definitely will.